24.6. Fetching a page¶

The web works with a metaphor of “pages”. When you put a URL into a browser, you see a “page” of content.

For example, if you visit https://github.com/RunestoneInteractive/RunestoneServer, you will see the home page for the open source project whose contents are used to run this online textbook.

The browser is just a computer program that fetches the contents and displays them in a nice way. If you want to see what the contents are, in plain text, right click your mouse on the page and select View source, or whatever the equivalent is in your browser.

24.6.1. Fetching in python with requests.get¶

You don’t need to use a browser to fetch the contents of a page, though. In Python, there’s a module available, called requests. You can use the get function in the requests module to fetch the contents of a page.

Note

For illustration purposes, try visiting https://api.datamuse.com/words?rel_rhy=funny in your browser. It returns data in JSON format, not in HTML. Your browser will display the results, information about some words that rhyme with “funny”, but it won’t look like a normal web page. Then try running the code below to fetch the same text string in a python program. Try changing “funny” to some other word, both in the browser, and in the code below. You’ll see that, either way, you are retrieving the same thing, the datamuse API’s response to your request for words that rhyme with some word that you are sending as a query parameter.

24.6.2. More Details of Response objects¶

Once we run requests.get, a python object is returned. It’s an instance of a class called Response that is defined in the requests module. We won’t look at it’s definition. Think of it as analogous to the Turtle class. Each instance of the class has some attributes; different instances have different values for the same attribute. All instances can also invoke certain methods that are defined for the class.

In the Runestone environment, we have a very limited version of the requests module available. The Response object has only two attributes that are set, and one method that can be invoked.

The .text attribute. It contains the contents of the file or other information available from the url (or sometimes an error message).

The .url attribute. We will see later that

requests.gettakes an optional second parameter that is used to add some characters to the end of the base url that is the first parameter. The .url attribute displays the full url that was generated from the input parameters. It can be helpful for debugging purposes; you can print out the URL, paste it into a browser, and see exactly what was returned.The .json() method. This converts the text into a python list or dictionary, by passing the contents of the .text attribute to the

jsons.loadsfunction.

The full Requests module provides some additional attributes in the Response object. These are not implemented in the Runestone environment.

The .status_code attribute.

When a server thinks that it is sending back what was requested, it sends the code 200.

When the requested page doesn’t exist, it sends back code 404, which is sometimes described as “File Not Found”.

When the page has moved to a different location, it sends back code 301 and a different URL where the client is supposed to retrieve from. In the full implementation of the

requestsmodule, thegetfunction is so smart that when it gets a 301, it looks at the new url and fetches it. For example, github redirects all requests using http to the corresponding page using https (the secure http protocol). Thus, when we ask for http://github.com/presnick/runestone, github sends back a 301 code and the url https://github.com/presnick/runestone. The requests.get function then fetches the other url. It reports a status of 200 and the updated url. We have to do further inquire to find out that a redirection occurred (see below).

The .headers attribute has as its value a dictionary consisting of keys and values. To find out all the headers, you can run the code and add a statement

print(p.headers.keys()). One of the headers is ‘Content-type’. Some possible values aretext/html; charset-utf-8andapplication/json; charset=utf-8.The .history attribute contains a list of previous responses, if there were redirects.

To summarize, a Response object, in the full implementation of the requests module has the following useful attributes that can be accessed in your program:

.text

.url

.json()

.status_code (not available in Runestone implementation)

.headers (not available in Runestone implementation)

.history (not available in Runestone implementation)

24.6.3. Using requests.get to encode URL parameters¶

Fortunately, when you want to pass information as a URL parameter value, you don’t have to remember all the substitutions that are required to encode special characters. Instead, that capability is built into the requests module.

The get function in the requests module takes an optional parameter called params. If a value is specified for

that parameter, it should be a dictionary. The keys and values in that dictionary are used to append something to

the URL that is requested from the remote site.

For example, in the following, the base url is https://google.com/search. A dictionary with two parameters is passed. Thus, the whole url is that base url, plus a question mark, “?”, plus a “q=…” and a “tbm=…” separated by an “&”. In other words, the final url that is visited is https://www.google.com/search?q=%22violins+and+guitars%22&tbm=isch. Actually, because dictionary keys are unordered in python, the final url might sometimes have the encoded key-value pairs in the other order: https://www.google.com/search?tbm=isch&q=%22violins+and+guitars%22. Fortunately, most websites that accept URL parameters in this form will accept the key-value pairs in any order.

d = {'q': '"violins and guitars"', 'tbm': 'isch'}

results = requests.get("https://google.com/search", params=d)

print(results.url)

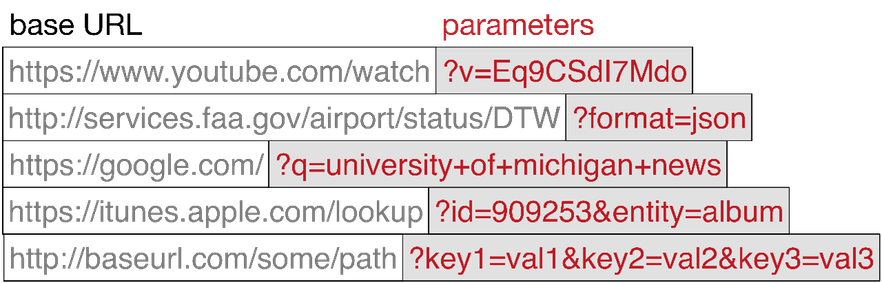

Below are more examples of urls, outlining the base part of the url - which would be the first argument when

calling request.get() - and the parameters - which would be written as a dictionary and passed into the params

argument when calling request.get().

Here’s an executable sample, using the optional params parameter of requests.get. It gets the same data from the datamus api that we saw previously. Here, however, the full url is built inside the call to requests.get; we can see what url was built by printing it out, on line 5.

Check Your Understanding

- requests.get("http://bar.com/goodstuff", '?", {'greet': 'hi there'}, '&', {'frosted':'no'})

- The ? and the & are added automatically.

- requests.get("http://bar.com/", params = {'goodstuff':'?', 'greet':'hi there', 'frosted':'no'})

- goodstuff is part of the base url, not the query params

- requests.get("http://bar.com/goodstuff", params = ['greet', 'hi', 'there', 'frosted', 'no'])

- The value of params should be a dictionary, not a list

- requests.get("http://bar.com/goodstuff", params = {'greet': 'hi there', 'frosted':'no'})

- The ? and & are added automatically, and the space in hi there is automatically encoded as %3A.

requests-6-3: How would you request the URL http://bar.com/goodstuff?greet=hi+there&frosted=no using the requests module?

- resp.json()

- .json() invokes the json method

- resp.json

- .json refers to the method, but doesn't invoke it

- json.dumps(resp.text)

- dumps turns a list or dictionary into a json-formatted string

- json.loads(resp.text)

- loads turns a json-formatted string into a list or dictionary

- json.loads(resp.url)

- loads turns a json-formatted string into a list or dictionary, but .url returns the url used to get the response, not the text of the response.

requests-6-4: If resp is a Response object returned by a call to requests.get(), which of the following is a way to extract the contents into a python dictionary or list?