Preface¶

Today, it is hard to imagine life without computers. We carry them in our pockets, read with them on the couch, and use them on our desk at work. Computing is the Swiss Army knife of the 21st century: a convenient tool that can be used to solve a wide array of problems. The original computers were large and limited in function: nothing more than very basic calculators. The military was the first to find some of the many applications of this technology: made small, computers could be used to improve the precision of bombing; made large and (relatively) powerful, they could be used to break military codes. As computers continued to grow in power and drop in price, many more peaceful applications were found:

Scientists in both natural and social sciences can use them to analyze vast quantities of data. For example, astronomers are able to identify distant stars in large images of the sky and sociologists are able to analyze the behavior of all the citizens of a country.

Artists and students of literature can use them to analyze great works, to find patterns in them that the human eye or ear had missed and use them to algorithmically generate some new works (examples from literature[1, 2] and music).

Business people can use them to instantaneously keep track of the health of their business across the globe and analyze past behaviors to better prepare for the future.

Doctors and medical researchers can use them to track the effect of new medicines across vast populations of patients.

Software engineers can use them to create apps and websites that attract billions of users.

Today, the amount of computing power and the volume of data available to us is staggering. The field of machine learning is just beginning to harness this power and data and is transforming the field of computer science. At one level, machine learning, allows programs to do for themselves what programmers have had to do for years, which is to recognize complex patterns in the data. Machine learning algorithms are now routinely doing better than humans in tasks like reading X-rays, or recommending a restaurant to try.

This course is about exploring the use of computer programs to solve these kinds of problems, whatever your area of interest and major might be.

To do so, this book will teach you how to understand and create computer programs in Python. Python is a programming language that is in wide use both for professional software development and in education. In the professional world, it is used for anything from creating small scripts that rename files in a folder, to developing full web applications such as YouTube, SnapChat and DropBox. In the world of education, Python is a popular language because of its relatively simple syntax, its robust set of built-in functionality and its beginner-friendly error messages. For all these reasons and more, Python has become widespread in the world of data science and machine learning as well; in fact, it is the principal language of TensorFlow, Google’s open-source machine learning library.

At the beginning of each chapter, we will outline for you the learning goals and objectives that should be accomplished once you have gone through the chapter. And, throughout the textbook, you will find projects that connect what you have learned to solving real world problems.

Understanding computer programs requires orderly, logical, mechanistic thinking. Programs are just sequences of actions to perform; when executed, they transform input data into output data:

numbers turn into other numbers (e.g. basic math operations like sin or log)

images turn into words or numbers (e.g. a cell phone photo of a diseased-looking leaf of a plant becomes the name of the disease affecting the plant or the number of whiteflies infesting it)

images turn into other images (e.g. filters in Instagram)

words turn into tables (e.g. reporting the number of times each character speaks in Shakespeare’s works)

numbers turn into 3D models of great works of art (e.g. Stanford’s Michelangelo project)

Get in the Learning Zone¶

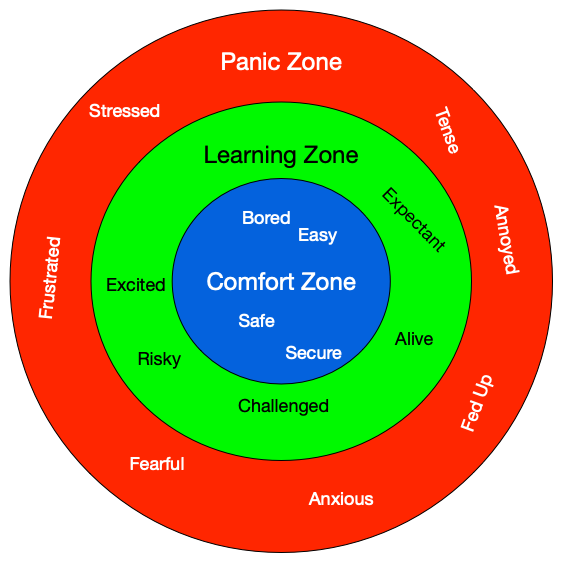

Programs execute very reliably, and very quickly, but not creatively. Computers do what you tell them to do, not what you mean for them to do. Thus, understanding computer code involves a lot of mental simulation of what will actually happen, not what you wish would happen. This can be frustrating at times but it’s something that you will get better at with practice. As you go through the activities in this class, some will be easy for you to complete, i.e. in your comfort zone. Being in your comfort zone is nice but it probably means you are not learning very much. More challenging activities will encourage you to think through the problems and to refer back to the reading to allow you to enter your learning zone. This is the zone that you strive to be in for as much of the course as possible. Beyond your learning zone lies the panic zone where the problem overwhelms your ability to grow and learn. If you find yourself in the panic zone, please seek help from your instructor and/or classmates: none of the activities in this book are intended to stump you. As you understand how to solve some simpler problems, you will develop the ability to join these solutions together to solve increasingly challenging problems with real-world applications.

In addition to mechanistic thinking, writing computer programs requires creative problem solving or the ability to identify a complex situation, think creatively about possible solutions, and express those solutions clearly and accurately. As it turns out, the process of learning to program is an excellent opportunity to practice problem solving skills you can use in other parts of your life. We sincerely believe that the combination of knowledge of Python, creative problem solving skills and expressing those solutions in such a way that a computer can effectively carry them out (computational thinking) will make you more productive and efficient in tackling your work in future classes,whether in Computer Science, Business, Psychology or History. And it may even pique your interest in becoming a Data Scientist or a Computer Scientist.